Powerful Delusions

On telling ourselves we're winning. By Raziye Buse Çetin

Narratives are social constructions. While they ‘reflect a shared interpretation of how the world works,’ narratives, in turn, shape the world. As one of the keys to our humanity, they stir emotion and empathy, influence and mobilise people, bring us together. Equally, they can divide and dominate, supporting unequal structures that exert power over others. When dominant narratives are repeated, they create systems that are so familiar they are invisible. They influence access to rights, privileges, economic resources, opportunities and policies in ways we have numbed ourselves to noticing. They can make institutions seem inevitable, legitimise certain solutions and make the world feel preordained. Narratives about technology are no different. As Nushin Yazdani and Ulla Heinrich write:

Our ideas about technology also shape technology. Likewise, when we call data ‘the new oil’, as researcher Maya Ganesh puts it, it shapes how we see data and work with it. ‘Such metaphors determine how a technology is developed, built, and will be regulated (or not regulated)’, she writes.

– ‘What Does our feminist future look like?’, Dreaming Beyond AI

‘We will know we are winning if…’

At the Digital Futures Gathering in Berlin, we spent two full days breaking down the dominant narratives about technology and drafting sustainable, fair and inclusive digital futures. With more than 50 members of digital civil society present from across the world, we challenged technological determinism and imagined the digital futures we actually want. In the course of sharing and building upon these desirable digital futures, we were asked to complete the sentence ‘We will know we are winning if…’ People gave great answers, taking strong positions based upon equity and freedom, often mixed with a tiny bit of melancholia. When it was my turn, I felt anxious and blurted out, ‘What if we are already winning?’

I want the future, now.

I felt naïve – yet, I wanted to believe. It was as if we could not afford to wait any more. I wanted The Future now. Could leading ourselves to believe that we are already winning constitute the kind of cocky resistance found in the #delusionaltiktok videos ?

Perhaps being delusional is a reflection of the socio-political moment we find ourselves in: living through a pandemic, facing the global effects of war, and dealing with rising inflation that has made the cost of living nearly unbearable. Everyone I know is exhausted, working hard, and at times, concocting an illusion of grandeur just to get by.

– Clarissa Brooks ‘On TikTok and in life it’s time to be delusional’

… to which I would add the climate crisis and deepening inequalities. The #delusionalgirl ‘manifests’ a boyfriend, money and opportunities – while she knows that her current reality does not match her desired reality, she chooses to act like she is already there. Lauren Berlant writes of the tension between the pitfalls of delusion and the way it can afford space to shape better realities.

A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing. It might involve food, or a kind of love; it might be a fantasy of the good life, or a political project. It might rest on something simpler, too, like a new habit that promises to induce in you an improved way of being. These kinds of optimistic relation are not inherently cruel. They become cruel only when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially.

– Lauren Berlant Cruel Optimism

Is #delusionalgirl a rebellion or a last-ditch attempt to maintain the dream of the long-lost ‘good life’?

When I said ‘What if we are already winning?’ was I deluded in thinking we can ‘manifest’ the digital futures we want, or is that kind of thinking exactly what’s needed to bring them about? Maybe it can be both, and that’s okay.

Escaping linear temporalities

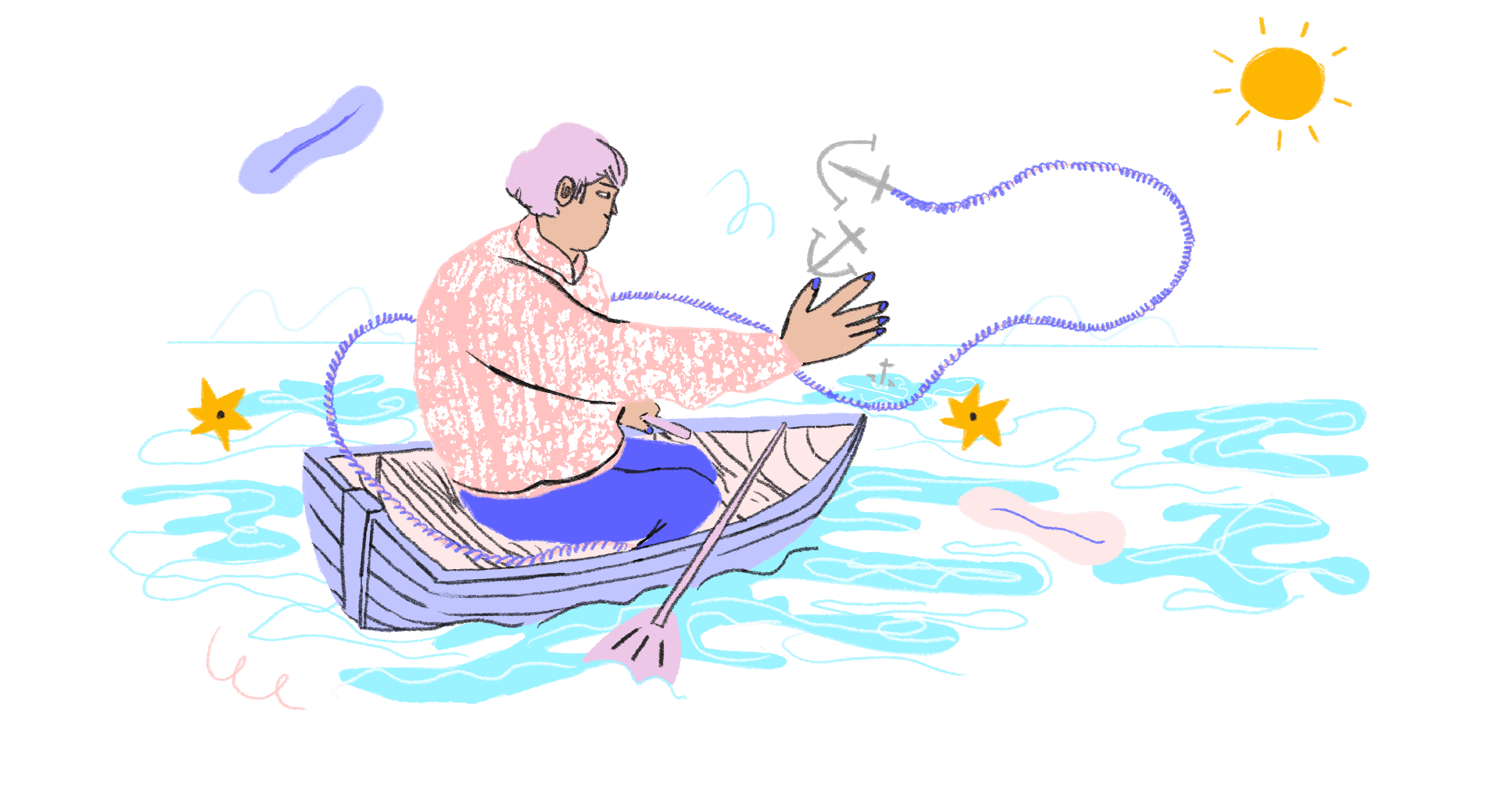

When I took a step back and thought about how I imagined desirable digital futures, I couldn’t help but have in my head the imperfect image of a very particular motion. I was on a boat, looking at the horizon, throwing a heavy anchor at the point where I wanted to be and pulling myself towards it. I know boats don’t move this way, but the image itself was important. My desirable future was somehow a fixed point in the unknown, and the action of getting there required force and tenacity.

Still, something was not quite right with the metaphor. It was only after an encounter following Heba Y. Amin and Nelly Y. Pinkrah’s panel at AI Anarchies Autumn School that I realised that how we envision and create future narratives matters as much as their substance. Powerful narratives that inspire change depend on inspiring thinking, on feeling and acting differently. My ‘futures-hunting’ was limited because it followed a linear conception of temporality, akin to the ‘arrow-like nomadism’ coined by Edouard Glissant:

In contrast to arrowlike nomadism (discovery or conquest), in contrast to the situation of exile, errantry gives-on-and with the negation of every pole and every metropolis, whether connected or not to a conqueror’s voyaging act.

– Édouard Glissant Poetics of Relation

Instead of pitching towards the future with an ‘arrow-like nomadism’, what would ‘errantry’ allow me to think, feel and act like in the present? Creating powerful narratives of digital futures is imperfect errantry: it revisits the archives to rewrite the past(s) as much as it envisions the future(s). And since the present enfolds both the past and the future (without a capital p or f), it is also about amplifying what exists in the here and now, even though it might feel like cultivating a cruel attachment to hope.

Raziye Buse Çetin is an independent AI ethics and policy researcher and consultant. Her work is grounded in critical epistemologies such as intersectional feminism, Science and Technology Studies (STS), postcolonial studies and decoloniality.